FEATURE: MILENNIUM DEVELOPMENT GOALS

Picture courtesy flickr Lifting the FogHOPE is buried below smoke and fog. Dark narrow streets wind around stockpiled shacks.

For many living in Alexandra, one day spills into the next, with no light at the end of their existence. Their neighbours are unemployment, hunger, personal suffering and crime.

Still for others, all hope is not lost in “the dark city”. Some are trying to forge forward, despite their circumstances.

Often relief, in communities like Alex, does not come from large, elaborate initiatives and funding; but rather from small initiatives that uplift the lives of individuals.

As William Easterly, a professor in economics at New York University and formerly a senior research economist at the World Bank noted in his book – The White Man’s Burden: “Sixty years of countless reform schemes to aid agencies and dozens of different plans, and $2.3 trillion later, the aid industry is still failing to reach the beautiful goal [of making poverty history]. The evidence points to an unpopular conclusion: Big Plans will always fail to reach the beautiful goal.”

Easterly believes solutions for issues like poverty can be found within “Searchers” – people who believe that only “insiders have enough knowledge to find solutions, and that most solutions must be homegrown.”

Home grown local solutions include initiatives like the Ballet Theatre Afrikan (BTA) Company and imaginationlab. These give hope and change the course of lives. Young hopefuls joining these programmes are taught skills that will allow them to become self-sustaining and provide a better life for their offspring.

“I have so many kids coming out of Alex. I have changed their lives. I have changed their family. By becoming involved in ballet, you have changed an entire family through one child. You are changing the whole fabric of that society. Change comes about by changing one person’s life, not the masses,” explained Martin Schönberg, retired ballet dancer and artistic director of BTA.

In 2000 at the United Nations Millennium Summit, the world’s leaders set out to improve living conditions of those living on the continent by 2015. They identified eight key areas – called the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) – with the common goal of creating human dignity and a world free of poverty and injustice.

Post 1994, South Africa has been marked by large economic growth. And many initiatives have contributed to improving the livelihood of those that had little access to basic necessities in the apartheid years.

But life in Alexandra has remained more or less unchanged.

Dogged by crime, violence, overcrowding, lack of infrastructure and high unemployment from the 1930s, Alex today still struggles with the same issues.

Gauteng’s oldest township, continues to be one of the poorest in the region, even though it is only 3kms away from Sandton, one of Africa’s wealthiest suburbs.

An influx of youth, in search of employment in Johannesburg, contributes to exacerbate living condition for those living here.

Unofficial estimates figures report unemployment to be in the region of 60%, more widespread among women (40%) than men (19%) and the average household income is about R1 029 per month.

Old Alex is mainly characterised by informal dwellings, shacks and hostels and the 7.6 square kilometres over which Alex stretches houses 350 000 people or 45 000 per square kilometre, against the urban norm of 2 500 per square kilometre.

As most shacks are not connected to the electricity grid, inhabitants resort to illegally tapping the main power lines. Only about 65% of households have access to piped water. And less than 20% of households have access to private toilet facilities.

It is against this backdrop, that the value of the work that the BTA and imaginationlab do injects some hope.

Art and culture play an important role in creating sustainable human development. And with the South African Department of Education including it into the school curriculum its importance for developing a nation becomes evident.

Schönberg started BTA in Alexandra 17 years ago, after a dinner guest said “it’s a pity about the blacks, they got wonderful rhythm, but unfortunately they really can’t do classical ballet.”

The company has received praise both locally and internationally for producing black dancers of world class standard and continues to look for talent from previously disadvantaged sectors of society.

“It was something I needed to do, and it was something that the children yearned for. They loved it,” Schönberg realised after starting BTA in Alex.

Schönberg believes that those children training under his guidance are not just getting another “art class”, but a whole new way of life. “Understanding the whole package of what makes a ballet dancer,” is important, he explained. Aspects taught include music, history and even the anatomy of what makes each dancer unique.

Dancers receive classical training as well as training in contemporary dance, jazz, Spanish and Afrofusion, which consists of a mix of traditional African dance and other styles.

Picture courtesy www.joburg.org.za

Thirty children are selected to train with BTA in Alex each year. Classes are free and leotards and shoes are donated by the school. Children are also given a meal before each class to improve their concentration.

It is hard work that will one day pay off as “many have gone on to dance internationally,” he said. Classes take place, four afternoons a week. Each is two hours long.

The objective is to develop professional dancers, choreographers and dance teachers from within under-resourced communities in South Africa that will be able to be employed locally or internationally.

“The need for this academy, resulting in the production of dancers of an international standard that can go out into the marketplace and earn their living from dance, has been identified by the community and a solution has been requested repeatedly over many years,” said Paula Kelly, the previous administrative director of BTA.

“The academy will, in addition, produce a number of qualified teachers of dance from the community,” she said.

Another initiative operating out of Alex is the imaginationlab, a facility that gives school leavers the opportunity to discover their creative strengths and passion when considering careers in creative fields like design, fashion, copy writing and photography.

The imaginationlab was borne from a dream that Gordon Cook and Andy Snyman had to help youth discover themselves through their creativity and to impart valuable life skills.

McDonald Musimuko, a student at the lab in Alex, said: “For those who finish school and are brain stuck, that do not know what to do, it [the imaginationlab] gives you a good idea of what you want to do.”

As part of his dream, Cook wanted to put these young adults “into a sandpit and give them lots of toys to play with to stimulate their creativity” by exposing them to different creative stimuli that would help them find a niche through which they would be able express themselves creatively to sustain a living.

Cook said: “From a macro perspective, the purpose of the lab is to bring previously disadvantaged talent into the [advertising, creative and brand building] industry by creating a ladder for them to climb that gives people the opportunity to climb into a field where they naturally belong.”

Previously, “talent was literally just sitting on the street, falling through the cracks,” but the labs have helped to create awareness that there are actually many opportunities for creative children in underprivileged societies, Cook explained.

Each class consists of around 25 – 30 students and around 100 hopefuls apply to each of the five centre’s each year. Selection is based on demonstrating individual creativity by answering a brief.

“The lab and Vega [who administer the lab] are not based on forcing an outcome on students but rather allows them to engage with creativity as a process,” Cook explained.

“They put your head into everything, branding, copy writing, design. You also find out about yourself, and learn about who you are and what you like, you learn about yourself,” said Musimuko.

“I am having a lot of fun. After finishing matric I was caught up with other things, and I didn’t know what to do with my life. It made me realise that there’s more to life than to sit around and wait, thinking that things will come to me. It made me realise this is who I am and this is what I want to do,” he said.

Students attend the lab for free and those that have to travel are provided with a monthly allowance that will help them to cover their travelling costs.

The labs are financed through collections made from the Media Advertising Publishing Printing Packaging (MAPPP) SETA and from agencies and corporates that provide Vega with funding, internship programmes and send employees to teach at the labs.

Corporates have used their involvement in the labs to create mentorship programmes within their organisations – that helps to sustain accountability from individuals that teach at the labs – and helps with their corporate social investment (CSI) in underprivileged communities.

The first lab was run from Vega in Benmore, after which Cook started rolling out the labs to other areas including Alex. Today there are five, with plans to open many more across all areas in South Africa. For Cook, it is important the labs partner with local communities to help to uplift them.

Slowly the fog starts to lift over communities like Alex.

FEATURE PROFILE: ALICE BROWN

A real life “she-ro”

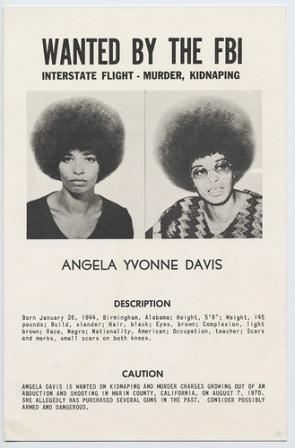

LOOKING at Angela Davis next to an African American attorney on the front page of The New York Times conjured up a dream of becoming a civil rights lawyer for 14 year old Alice Brown.

“Here was my ‘she-ro’ in handcuffs, going to court – and next to her was this African American man and he was her attorney. That was the first time in my life I realised that there were African American attorneys,” recalled Brown.

Davis, a racial activist, came under the spotlight in August 1970 when the FBI listed her as one of the ten most wanted criminals in the United States. She was implicated in a failed attempt to free prisoners from Soledad Prison in which four people were killed when the gun used in the incident was traced back to her. Davis went on the run and was arrested only two months later.

At that point in Browns life, she had only come into contact with a handful of African Americans teachers and knew that there were African American women practicing as nurses.

“And I knew of African American preachers, because Sunday morning is the most segregated hour in all of America. But male or female I had not seen or heard of an African American attorney before.

“And I said, damn, this is what you can do! This is what you can be! The kind of person that defends Angela Davis! That is what I want to do.”

But she would only litigate and practice law 20 years later in 1990.

Brown is the Southern African representative for the Ford Foundation, which means “I run the office for the region and I am also the grant maker for philanthropy and arts and crafts.”

She got “stuck” in South Africa, when while “on sabbatical for a year” as a human rights fellow at Harvard “with six months worth of money”, the Ford Foundation asked her to consult for them for six months.

“So I’m bouncing back between South African and Cambridge [Massachusetts] and it must have been month number five, when the then representative of this office, John Gerhard, came to me and said to me: Alice, I’m about to lose a staff member and I need some help.”

“And I said to him, you know John I am on sabbatical and I am probably going to just go back to the states eventually. But okay, since I am running out of money and I could use it I could do this for four or five months and then I’ll finish off my sabbatical and then I’ll go back to the US.”

Brown fiddles with the coasters on the table. Organising and re-organising them into patterns.

But during her fourth month here she had an epiphany.

“I said to myself, what are you going to do? You are going back to where to do what?”

Brown – a trained civil rights lawyer with a particular interest in South Africa – decided that being in South Africa during its transformation was an opportunity which doesn’t present itself often. And she decided to stay on.

“I was just saying: man, there is all this stuff going on why the hell would you want to go back to the US to beat your head against that wall?”

At the time the Constitutional Court was being established and the Constitution was being drafted.

“And you have social and economic rights that are being written into the Constitution, very explicitly in a way they don’t exist in the US,” recalled Brown.

“You can be in a place where you’re starting from scratch, starting with a clean slate.

“In an atmosphere where you would be helpful; helping to facilitate the development of the human rights arena and the development of a progressive human rights culture that cannot happen in the US right now.

“What is it? ‘South Africa alive with possibility.’ I heard the ad and I bought into it.”

So the “light bulb went off” and Brown stayed on in South Africa at the Ford Foundation, even though it meant that she wouldn’t be able to practice law or litigate.

Brown had previously worked at the Foundation in New York – from 1986 to 1990 – and was responsible for grants to black South Africans during the apartheids years.

And at the time, she believed it was destiny.

She had decided that after completing her degree, she would first complete a Masters degree in African history at Northwestern University before returning to New York University to complete her law degree.

“It was a great disappointment to my father who didn’t understand it at all,” recalled Brown. “As since I was 14 I had declared that I was going to be a lawyer. So what the hell did grad school and history have to do with being a lawyer? Why didn’t I just stay on track?”

Brown however believes that “I was ahead of my time”, since for her, to be a good civil rights lawyer it was necessary to have a good understanding of African-Americans history first.

“This was 1978, ’79, ’80 and people were looking at me in grad schools and law school like I was crazy,” recounted Brown.

“They would say to me: in terms of the law and those issues, you would need to look at international law. And as a young professional you don’t get to work in the United Nations (UN), you need to be seasoned and older and there really is no way to marry these two.”

But she stood her ground.

“So I stayed a year [at grad school] and then went to law school as I said that I was going to do” and specialised in public interest law.

In the eighteenth month of her clerkship she heard about the position at the Ford Foundation.

The job spec required someone with a social science background in African history or African development and a law degree.

“So I said that’s my job. That’s written for me. And I’ve never felt that way before in my life, and I said somebody wrote that job for me. And I applied and amazingly I got the job.”

Founded in 1936 by Edsel and Henry Ford, the Foundation operates as an independent, non-profit, non-governmental organisation with 12 offices in Africa, Asia, Latin America and Russia.

During the apartheid years, the Foundation was particularly involved with the Centre for Applied Legal Studies (CALS) at Wits, the Black Lawyers Association, Black Sash and a number of higher education programmes.

“At that point we were particularly trying to help increase the numbers and expand the educational credentials of black South Africans.”

This included sponsoring scholarship programmes that were taking black students to the States to complete Masters and PhD degrees and local internship and fellowship programmes that allowed black students to complete degrees.

Today, the foundation is still active in higher education, but initiatives also include philanthropy, human rights issues, governance, economic and environmental development, arts and culture and sexual health on which it spends about $16 million each year across South Africa, Mozambique, Namibia and Zimbabwe.

After 5 years as a grant maker, she decided that it was time to pursue her dream as a civil rights lawyer.

“In about 1989, I started to feel itchy, like okay, this is a great job and I’m doing great things, but I’m a grant maker. I’m funding public interest law centers, I’m funding human law attorneys to do things … you – as a donor – are not the doer, you are funding, helping those who do.”

Having completed her law degree, passing her bar exam and finishing her clerkship with the federal law of appeal, she was a qualified as lawyer but had never practiced law.

“And I need to do it sooner rather than later,” she decided. “Because the longer I take to go back to it the less credibility I will have to get back into the field.”

So began Brown’s five years as a litigator at the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) Legal Defense and Education Fund. She was responsible for the legal aspects of housing conditions, environmental justice and poverty issues for African-American communities.

“It was something I was very passionate about and nearly everybody I worked with in that agency was as passionate about. You could literally just work 24 hours a day, seven days a week and still not do enough or not give enough.”

But after five years, she decided that she needed some time out.

“It was very, very demanding and exhausting and all consuming. I decided to take a break. So I took a year’s sabbatical, with six months worth of money.”

And that is how she ended back at the Ford Foundation.

Brown, a single mother, has an eight year old son, Ayanda, and even though she is a dedicated professional, “my responsibility is him”.

“His dad is around and sees him every other weekend – ‘Disney Dad’.

“You do the discipline, you do the hard work and they come in and ‘here’s tickets to World Cup Soccer’, or ‘here’s that PlayStation that you wanted’. And you’re ‘but he doesn’t need it’. And he’s like, ‘he wanted it’.”

“I like parenting for the most part. I say to my kid, I think I’ll keep you, I think the warrantee has run out. Although, every once in a while I threaten to take him back and get my money back and he says you know it’s against the law.”

Brown tries to spend as much time with Ayanda as possible.

Generally she gets up early after having woken up two or three time during night to “send out notes on my crackburry” or make notes on her laptop.

And every morning she cooks them oatmeal and fruit for breakfast. After walking him to school, she gets ready to go to the office “to be faced with 15 000 things”.

“I come in with my list of things I want to do, that I want to accomplish, and then life is what kicks in when you are sitting around planning other things,” she said.

“I get phone calls and I get staff members, and I get e-mails from New York saying we need x yesterday, and can you meet with so and so who’s at the front door who hasn’t got a meeting. So, I come in and have a crazy day.”

She generally tries to be home around 5.30pm to spend some time with her Ayanda – to share dinner and play a couple of games – before putting him to bed after which she tends to either continue working or “crashes”.

Brown describes her life growing up as very different from her sons. She grew up in a town with in New Jersey, 20 minutes from Manhattan, called Hackensack with her four sisters and surrounded by cousins, aunts and uncles.

“We were always running from one auntie’s house to one uncle’s house to the park with my cousins.”

According to Brown, today, everything is organised. Nothing is as spontaneous. And as children, they had a chance “to use your ingenuity in a way that’s different” from today.

Today, “you have to arrange a play date. You have to arrange to go to the movies or the mall.

“We would literally just go the park and strike up a game, like something like Double Dutch, hide and seek, what have you.”

Or they would collect and return soda bottles to the store so that they had money to go to see a movie.

For Brown this is an unfortunate part of the reality with which children today have to deal with.

“Times have changed.”

HEALTH & SCIENCE FEATURE:

JUVENILE IDIOPATHIC ARTHRITIS (JIA)

Old beyond your years

FROM the time she was two, Sarah’s* hands were funny. The small joints of her fingers are swollen and wobbly, like those of an 80 year old.

She is slower at getting up in the morning and her parents say she’s not very athletic, because she has never really wanted to participate in sport. They tried music. But she said that she didn’t really like to play the piano.

She has got deformities in her jaw and cannot close her teeth properly. Her neck is stiff and she is under-grown.

Sarah is only eleven and has suffered from arthritis for nine years.

Her condition, was only “fortuitously detected” recently, when her paediatrician was on holiday and she had to see someone else.

Since she did not know how to verbalise the pain, she grew up believing that this was the way that life was supposed to be.

For Dr Gail Faller, a paediatric rheumatologist, it is tragic that it took nine years for Sarah’s condition to be diagnosed, especially since she lives in a city with good medical services available.

Currently there are only four paediatric rheumatologist’s that are registered in the country: Faller runs a paediatric arthritis clinic at Chris Hani Baragwanath Hospital in Soweto, Dr Monica Esser and Chris Rainier-Pope are in Cape Town and Dr Kogi Chinniah is at the Nelson R. Mandela School of Medicine at the University of Natal.

To overcome the stigma that arthritis is an “old people’s disease” the Arthritis Foundation launched the Children Have Arthritis Too (CHAT) trust in 2006.

CHAT’s main purpose is to raise awareness about juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA), help with funding and provide a support network for parents with children suffering from arthritis.

As, according to Carin Dreijer-du Plessis, an occupational therapist (OT) specialising in arthritis; “the biggest drawback in treating juvenile arthritis is late diagnosis.”

“Parents know: if a child has a headache and a stiff neck, they should worry about meningitis,” Faller explained. “If he is drinking a lot of water and losing weight, check for diabetes. If he is bruising a lot and very unwell he could have leukaemia, it’s the same thing, if your child has joint pain for six weeks, he could have childhood arthritis.

“For me it’s such a sad thing. It’s so treatable, but it’s so missed. You can virtually cure these kids. You diagnose it clinically by listening to the parents, by listening to the child, by looking at the child.”

For Lisa Clarke, “getting arthritis as a teenager was a bit of a blow. Like so many others still believe, I thought that arthritis was only something grannies got. I soon learned my lesson.”

JIA is defined as “the condition where one or more joints become inflamed (swollen, red and painful) for at least six weeks in children under 16, once other known causes of arthritis have been ruled out.”

“The earlier it’s diagnosed, the easier it is to get them into remission. If a child complains about a sore joint for more than two weeks, immediately seek help,” Faller advised.

“In South Africa we are under-diagnosing juvenile arthritis a lot. Eighty percent of children that end up at the clinic at Chris Hani Baragwanath Hospital have been missed for six months or more. Mostly children present in the same ways as adults do, but people struggle to diagnose it because as they say, children don’t get arthritis,” she said.

If a child is treated within three weeks after disease onset, they will be able to go into remission within six months. But even though it will be more difficult when it’s diagnosed later on, 90% of children will go into some form of remission once they are given the correct medication.

For Faller, “part of the problem is that children complain about these things, and we think that it’s normal for children to complain, and its not.”

Or, adds Dreijer-du Plessis “because a child has been living with it for so long, their whole body aches, so that they can’t identify the problem area any more. And therefore they don’t complain.”

According to studies done in the United Kingdom, around one in every 1 000 children has JIA, though more recent statistics from Australia, estimate that between one in 250 and one in 500 children in the world has some kind of arthritis which is undiagnosed.

“To me it must strike a chord in a doctor’s head when a child tells you that it takes 15 minutes to get going in the morning,” Faller explained. “Children are not stiff in the morning most adults are not stiff when they get out of the bed in the morning.”

Typical symptoms include: struggling to get going and stiffness in the morning, back ache, limping, struggling to write, the reluctance to use an arm or leg, swollen joints and persistent fever.

A common mistake made is confusing the disease with sports injuries. “Children – especially boys – are accused of spraining their ankles often. These are not sprained ankles,” said Faller. So, children, who seem to frequently suffer from a sprained ankle, should be checked for JIA.

Boys are also more often missed than girls, due to the perception that it’s more a women’s disease.

Arthritis often presents in exactly the same way as leukaemia. “If your child has lost weight, limps, has swollen joints, is pale – and you have ruled out muscle pain, sprains, growing pains – and the child has an infection, then I need to look if I’m dealing with a child with leukaemia or arthritis,” explained Faller.

And treatment is cheap.

“This is what kills me about this. It’s so cheap to treat,” said Faller.

Typical treatment, excluding therapy, will cost in the region of a R100 a month and mainly consists of two categories of drugs; those which control the symptoms of the disease and those which can affect the disease itself.

Arthritis drugs mainly aim to stop the inflammation process. Firstly they help to relieve pain and maintain movement within the joint and secondly, help to bring healing to the area, by removing the inflammation that is responsible for destroying the cartilage and bone.

“That’s why we talk about early treatment,” Faller explained. “If that joint is destroyed, it is destroyed, it’s finished – you have no more cartilage.”

Cartilage is what makes movement possible and “if you have lost your cartilage, you have bone on bone, and bone on bone fuses. It’s very painful and very stiff, you can’t move it.”

“If you can take away the inflammation altogether, the child’s body will heal. You are looking at all that inflammation that is destroying the cartilage, maintaining the joint space, maintaining the fluid and the cartilage and then the joint stays normal,” Faller continued.

It also recommended that every child goes for OT and physiotherapy, as “without it they are lost.”

For children with JIA, exercise is exceptionally important and the benefits of physiotherapy – improving function and increasing independence – can be seen within a few weeks,

Whereas, OT takes a holistic approach on the disease by assessing how everyday tasks – such as going to school, playing, and household chores – have been affected and recommending changes that aim to help a child maintain their independence.

An occupational therapist will also consider improving hand function through strength and range of movement or pain management techniques – such as teaching relaxation or other coping strategies, like wearing splints, occasional use of a wheelchair or making adaptations to their physical environment.

In addition podiatry is also recommended. Regular appointments with a podiatrist will help to avoid surgery in the long term, by making sure that a child is wearing the right shoes or insoles that provide support for ankles and ensure that the feet are properly formed which will help children to not damage their hips.

“The aim is to get the right diagnosis from the start, so that you can avoid having to send your child for surgery like hip replacements and tendon transfers,” Faller said.

A small group of children, about 10% – 20%, don’t respond to any treatment.

These children suffer from an adult form of arthritis and only respond to biological therapy.

Developed six years ago, biologics target individual cytokines or molecules involved in inflammation by either inhibiting or turning off the inflammation process at a cellular level.

“For the kids that respond to nothing else, these drugs are like miracles.” Faller marvelled. “It’s like it just melts in front of your eyes from the very first dose. These children are pain free, and it’s like switching something off. But that’s when it becomes expensive.”

Using biological therapy costs in the region of R5 000 to R10 000 a month, though most medical aids have started paying for it, if all other treatments fails. Alternatively, CHAT can also help to fund treatment.

For Faller, increasing awareness about the disease is key as this can help to avoid situations like Sarah’s.

October is World Arthritis month and currently South Africa is in its second last year of Bone and Joint Decade.

* Not her real name

Useful websites:

The American Juvenile Arthritis Organization (a council of The Arthritis Foundation)

http://www.arthritis.org/communities/juvenile_arthritis/about_ajao.asp

National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases Information Clearinghouse

http:// www.niams.nih.gov

Children’s Chronic Arthritis Association website

www.ccaa.org.uk

Donations to CHAT can be made:

* Via a bank deposit or electronic funds transfer. Banking details are as follows: The Arthritis Foundation, Standard Bank, Branch code 020909, Account: 070965226. Please mark EFT deposits with the word CHAT.

* Via an SMS.

– To make a donation of R30, you can SMS the word CHAT to 42602.

– To make a donation of R20, you can SMS the word CHAT to 40902.

Or to join a support group:

To find out more about the Johannesburg support group for parents and caregivers, contact Tel: (011) 726-7498.

Parents who would like to start or join similar groups in other areas of the country are requested to phone The Arthritis Foundation helpline on Tel: 0861 30 30 30.

TRAVEL FEATURE: NEW YORK CITY (NYC)

Your second home

EVER notice how President George Bush starts talking slower just as he’s about to make an important point?

“I used to think it was something he did for emphasis or to simplify a complex concept. But I now realise that he’s merely mimicking the way it was explained to him!” said Al Ducharme.

We were watching stand-up comedy at the Gotham Comedy Club as New York continued to work her charm on us. Slowly opening her bag of tricks – she drew us in under her spell – turning us into life-long fans, along with the 40 million others that visit her shores annually.

Merely calling New York a city with many attractions would not serve her well. This is an experience that is bound to stay with you forever. One you’ll look back on with a sense of dreamlike awe… wondering if it was real.

For the traditionalist, experiences range from standard attractions found in most guidebooks like cultural, dining, shopping, art or history. Or, for those adventurous enough to be led by a higher force, there’s a blank section under “expect the unexpected”.

Manhattan Island is best discovered on foot, which will allow visitors to immerse themselves into its vibrant and varied street culture.

“To its pedestrians, New York offers secret gardens off the driven path, glorious displays of art and architecture, spontaneous entertainment… [while] it punishes motorists with one-way streets,” The best things to do in New York, explained.

Although avoiding the subway, is to avoid New York’s “underground neighbourhood”.

In this confined space, you will come into contact with musicians that use it as a low-cost venue, to entrap and entertain instant crowds, hoping they might strike it lucky by being “discovered”.

Curious locals will “sense” your end locale and provide you with directions and handy travel tips, without ever asking for any.

Or it provides an express travelling experience that will allow you to escape from the heat and humidity that rule above ground, by sweeping you across the city in an air-conditioned carriage.

Obvious attractions include New York icons like Broadway, Central Park, the Statue of Liberty, Ground Zero, Times Square and the Empire State Building. But, even these “old favourites” have the ability to surprise and delight.

Every evening the Empire State Building turns into the world’s largest night light, engaging passers-by with different coloured lights that are projected onto the tower. Patriotic: red, white and blue for national celebrations or red and green for Christmas. Lights come on at sundown and – Cinderella-like – turn off at midnight, except for special occasions, when they shine until 3am.

Photo courtesy www.flickr.com

When looking at the Statue of Liberty on a postcard, it would be easy to make the mistake that she rules the Manhattan skyline along with all the other skyscrapers. But not so! She is only a far off non-entity, cast out onto her own little Ellis Island.

Or, did you know that when visiting the United Nations building you are standing on international territory? And while you’re there, feel part of history by visiting the Security Council or General Assembly room.

Alternatively, just roam the streets to discover a personal New York through moments so subtle, you might miss them if you took another route.

For us, one of these moments included walking past the Barnes and Noble at Union Square where we learned from a poster in the window that ex-president Bill Clinton would be there that evening for a book signing.

Taken up by the chance of meeting a world leader, we bought a copy of the book and joined the queue.

But he only shook my hand, and was now looking down to sign my book.

“I had not just spent a couple of hours in a queue and a whole day in anticipation to be snubbed with a half-hearted hand shake! I want a bit more of a reaction,” I thought to myself.

So, in attempt to goad more reaction, I wagered: “Greetings from South Africa.”

“You’re from South Africa,” he said taking the bait. “I was in South African a couple of weeks ago with Nelson Mandela. I met 200 wonderful children at his birthday party.”

“I like South Africa and visit there often. Did you know about the party?” he asked in his Southern drawl.

“Unfortunately not, as we didn’t crack an invite,” quipped my husband, James.

Walking away – we recounted every second of our conversation – incredulous that we actually just spoke to Bill Clinton, clutching our only evidence: a signed copy of Giving.

Or the day we blindly ambled onto a movie set. We had finally managed to track down Bread, a restaurant specialising in sandwiches, when suddenly we were frantically waved aside. A school bus camouflaged as a bee whizzed past us. It stopped and kids in bee costumes stampeded out of the bus. Roll camera, action, take two.

En route to our trendy dining experience in the Meatpacking District one night, searching for our restaurant, we accidentally wandered into the Chelsea Market.

Formerly the National Biscuit Company (Nabisco) this is where the first Oreo cookie was made 1912. This space has been renovated and today is an industrial-chic food arcade that sells home-baked breads, lobster, wine, artistically hand-decorated cupcakes and imported Italian foods.

Alternatively, get your favourite movie script from a street vendor. Buy designer clothes for a third of the normal price at sample sales. Watch people play chess on Washington Square or admire models posing for photos at Fashion Week. Or for some solitude, visit the Rose Main Reading Room in the public library.

In addition, New York offers many “taste bud” experiences.

“The hardest part about eating out in New York is the sheer choice,” says Time Out “It’s downright dizzying. You won’t be able to conquer the city’s culinary scene, but you can have some great meals trying.”

With 23 000 restaurants, café’s and bars in New York City, it is understandable that the choices available can be overwhelming. Add to this a large influx of immigrants – all with cuisine from their home country – and the choice becomes staggering.

“Genres from classic diner and Jewish deli fare to helplessly hip upscale celebrity-chef offerings and the authentic, ethnic flavours of Italy, France, Israel, Japan, South India, Brazil, Mexico… shall we go on?,” said the Lonely Planet New York City guide.

A simple and highly recommended experience for all first time visitors is eating a toasted sesame bagel with cream cheese from some hole-in-the-wall deli. Or going to Lombardi’s, the oldest pizzeria in town which, established in 1905, today still serves perfect thin, chewy crusted pizzas made in a coal fired oven.

Explore the Meatpacking District for chic dining or Clinton-Hell’s Kitchen for ethnic eateries. Or dine on the street by grabbing a pretzel – a meal itself – at a local street vendor.

Whatever, your experience, it’s easy to understand why mayor Bloomberg calls “New York the world’s second home”.

FEATURE PROFILE: JANE TAYLOR

Being Jane

IT’S 4.00am. The day has not broken yet. Most of Johannesburg is still asleep, enjoying their last fragments of sleep before starting the day.

Her head still feels fuzzy. But this is the time that Jane Taylor sets aside to tap into her creativity. And for producing her creative works. Like the well-guarded novel and a scholarly book in which she explores the meaning of “sincerity” that she is working on at the moment.

Taylor holds the Skye Chair of Dramatic Art and is the head of the multidisciplinary School of Arts at Wits. She has a PhD in English from Northwestern University in Chicago, and has held various fellowships including a Rockefeller Fellowship in Atlanta and a Magdalen Visiting Fellowship at Oxford.

She believes that her creativity is at its peak early mornings, around the time that the city starts to awaken to produce a new day.

“Working in the early mornings, allows you to draw on your unconscious,” she explained.

“Especially with something creative you need long chunks of silence. When doing something intellectual, it’s easy to dip in and out of it, but you need those long chunks of silence to explore creative work. To have the habit of the early start,” she continued.

Her days are packed with meetings, think tanks and a lot of philosophical work and discussions with students, institutions and the City of Johannesburg’s art scene. And with filling out forms, which she describes as a “legacy of the old apartheid system; to leave a paper trail that can be followed”.

At the end of the day, she loves to unwind by escaping to her home in Parktown, having intellectual discussions with her partner, David Bunn and taking their dogs for a walk through their neighbourhood. She and Bunn take several hours discussing “the crises of the day”.

Taylor loves spending time outside and connecting with nature. She grew up “in a rural way thinking that I could do anything I want”. And today she is still deeply affected by a “tremendous longing for real nature” having spent most of her youth on a mountain in Cape Town growing up.

For Taylor, moving to a small flat, in a city is unthinkable. “I realise that I need the ground. I get tremendously depressed when I am not growing anything. It gives me a tremendous sense; I have to put things into the ground. I really like to garden.”

“I have a 2 000 square metre garden, with a hundred rose bushes. It’s a lovely space. It has a farm style house, with a farm style garden. I grow beans, artichokes, tomatoes and brinjals. I really love gardening. That’s why it’s very difficult for me to imagine living in an apartment block”.

She sees her life growing up as “charming”, though she always had a sense of disconnection “growing up in cultures where I belong but I’m not part of, like growing up amongst Malay children”. Playing with them but not being part of their culture and their reality.

“I felt like there were extraordinary events that I had no real access to,” she recalled.

She distinctly remembers that next to their farm in Strawberry lane in Constantia there used to be a Muslim cemetery. “I used to hide in a Blue Gum tree and watch their lives. I felt that their lives were much more interesting”.

A very formative influence while she went to school, were “a group of four girls that were great story tellers” and used to act improvised stories out every day during break. “They were like goddesses … they captivated the whole school ground… so that very much defined me.”

Another big influence in her life was when she started attending drama classes at Mars Studio’s in Cape Town with Rita Mars. She used to take the train in from Constantia. Classes were from 10am to 12am on a Saturday.

“I knew I was going to be a performer. It’s fabulously transformative and introduces you to different worlds and influences.”

But when she went to university and started studying performance, she realised that it wasn’t what she really wanted to do, and she switched to a BA degree instead, majoring in English.

Drama “was not really who I was. It made me feel too vulnerable and exposed, and I did not enjoy that,” she said.

Taylor also has an inherent love for competitive games that involve risk. “I like cheating and getting away with it, especially poker. I put myself through university by playing poker.” Though she is not secretive or underhanded about her cheating, for her it’s a game in itself: telling people upfront she intends cheating and then getting away with it.

While she was busy with her honours degree, she met an “interesting tutor called David Bunn” whom she followed to the States and married.

For her, one of the highlights in her life is “the intellectual companionship I have with David Bunn. To discover someone who is really an ethical good human being, who is astonishingly intellectually rewarding, has been a great sustaining joy in my life.”

She is particularly interested in discovering “how we create our future based on a traumatic past”.

Her interest was first sparked when she was taking care of her father one day and she “heard this howling like an animal” after he had watched the World at War. Her dad had been captured in North Africa during World War II, but never spoke of this traumatic experience.

“For the first time, I understood the enormous terrain that my father was living with, that we didn’t know about. And it made me realise how uncaringly you can live with others, especially when we don’t understand the inner landscape that they have to live with daily.”

This interest also spurred her on to work through the transcripts from the Truth and Reconciliation to produce the Fault Lines exhibition and plays like Ubu and the Truth Commission and Confessions of Zeno directed by William Kentridge.

These all deal with how South Africans are trying to work through the wounds of apartheid while trying to make sense of how to create a better future for all.

Other works include inquiries around the representation of remorse at the Truth and Reconcilliation Commission and at the World Court, and more recently, she was awarded the 2006 Olive Schreiner award for her book entitled Wild Dogs.

Taylor believes that it’s important to maintain an active mind and continue to be active and involved in society.

According to her “one of the disastrous things that we as human beings do is that we think that we have reached a final point. I am very interested in never allowing that to happen. And if necessary, to change my circumstances to keep on provoking myself to have new conversations.”

“People need to find ways to engage with public debate. And I also think intellectuals need to engage with the public. So the people at Wits need to understand that they are actually in a public conversation.”

“In a way that’s how the arts manage, it has to always remember that it has a public audience. It is one of the reasons that the arts are so important to the university, since the arts are often the university’s public face. It’s between those spaces.”

She always loves reading. This love bloomed when in her teens she broke her spine and spend six months lying still.

“I couldn’t be in a house without books. I cannot imagine a space or a house without books. I go through phases where I read the latest literature, phases where I read renaissance plays, poetry, philosophy, so it’s a bit of every thing.”

As head of the School of Arts, she strives to instil optimism in students, as she believes it helps to overcome all obstacles that they might perceive otherwise.

“The content is just shaping them. [But it’s important] to make them feel that things will always be interesting and that they will always get rewards from challenges. The pleasures of being with people that are discovering their own power and themselves are astounding,” she continued.

“Modern condition seems like so many things are insurmountable. The biggest thing I need to pass on to my students is optimism. I think the intellectual goal is worth fighting for if they believe it’s surmountable.”

Leave a comment